One final dispatch of the year: https://open.substack.com/pub/sabinastent/p/the-q-symphony?r=ceu&utm_medium=ios

One final dispatch of the year: https://open.substack.com/pub/sabinastent/p/the-q-symphony?r=ceu&utm_medium=ios

I wrote about seeing the coven of Carrington, Horna and Varo in Osgood Perkins’ Keeper, for my newsletter: https://open.substack.com/pub/sabinastent/p/keeper?r=ceu&utm_medium=ios

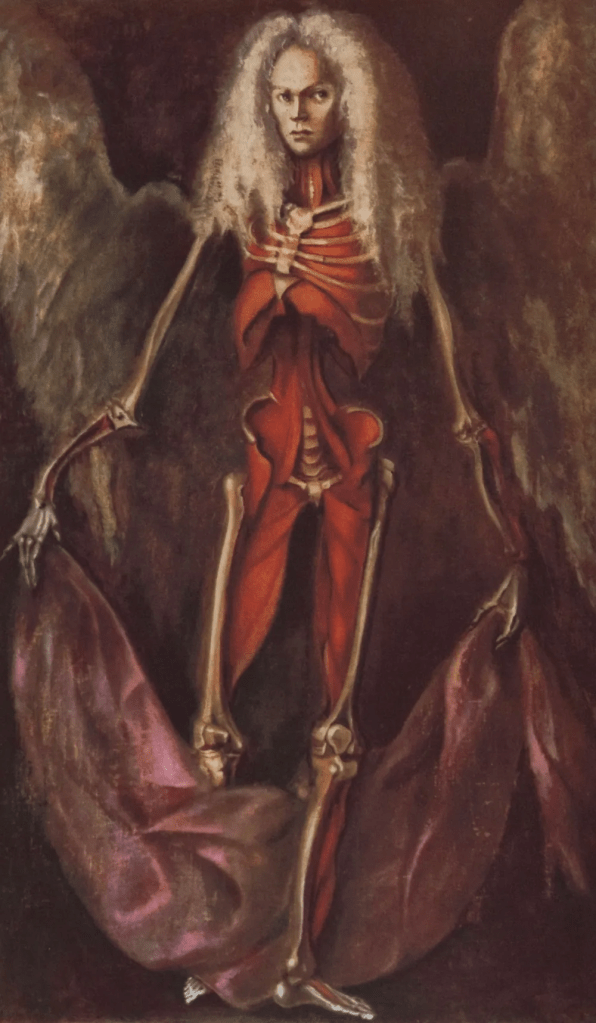

My latest newsletter is about Leonor Fini and GDT’s Frankenstein. Happy dia de los muertos. https://sabinastent.substack.com/p/lange-danatomie

It’s been a while but my latest newsletter is about Toyen: https://sabinastent.substack.com/p/relache

In an interview for the Criterion Channel, Michael Haneke described what sparked the idea for Benny’s Video. His candid explanation was, “I wanted to know what it was like”.

“It’s a sentence I read once in a magazine,” he said, “that told the story of a crime committed by a boy — it was a boy who killed another child or something like that. When the police interrogated him, that was his answer. And I was shocked by that.” Haneke spoke of collecting articles of this kind for the few years that followed, and the repetition of that sentence: I wanted to know what it was like.

“For me,” continued Haneke, “those are the words of a person out of touch with reality. When you learn life and reality only through the media, you have the sense that you’re missing something. If I see only a film, only images, even images of reality, a documentary, I’m always outside.” He wanted to be “inside”.

Riffing on the video game and handheld camera culture that came of age during the 1980s and continued into the 1990s, Benny’s Video (1992) – the second of Haneke’s first three feature films and the centre of his “Glaciation Trilogy” – succeeded The Seventh Continent (1989) and preceded 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994). The trio of film were described by Criterion as “exploring the relationship among consumerism, violence, mass media, and contemporary alienation,” to “open up profound questions about the world in which we live while refusing the false comfort of easy answers.”

Benny’s Video stars Arno Frisch as Benny, a teenager with a predisposition towards violent images and obsessed with recording equipment, who documents practically everything via visual and audio means. Benny’s parents encourage their son’s “hobby” by way of affection, overcompensating for their lack of tenderness at home by buying all his equipment, oblivious to their son’s voyeuristic fascination with violence and how they are fuelling his habit. This fascination leads to a violent incident, with Benny intentionally recording the encounter – and its aftermath – the entire time.

In her book, Michael Haneke’s Cinema: The Ethic of the Image, film scholar Catherine Wheatley wrote that Benny’s Video prominently features “metatextual troubling of levels of reality” by incorporating Benny’s handheld camcorder footage, sound, and static cameras into the film, the result of which creates an “extremely distanced, ‘objective’ relationship to the narrative.”

As Haneke explained, “with an image, you cut the imagination short. With an image you see what you see, and it’s “reality.” With sound, just like with words, you incite the imagination, and that’s why, for me, it’s always more efficient”. “The image is the distancing and the sound is the manipulation,” he continues. “Using these two means, it gives an impression that’s complex enough to destabilise the viewer.”

Premiering at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival and opening the following Autumn at the 1993 New York Film Festival, Stephen Holden of The New York Times praised Frisch’s performance, writing, “what gives the film a chilly authenticity is the creepy performance of Arno Frisch in the title role. Cool and unsmiling, with a dark inscrutable gaze, his Benny is the apotheosis of what the author George W. S. Trow has called “the cold child,” or an unfeeling young person whose detachment and short attention span have been molded [sic] by television.” The controversial yet acclaimed film went on to win the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) Award at the European Film Awards.

Frisch continues this sadistic streak when he reteamed with Haneke for 1997’s Funny Games, which is interestingly the only one of Haneke’s films the director himself describes as lacking a semblance of guilt, something his other films all contain.

Haneke always likes to leave open the answer to “why did someone do something?” as open as possible. “In this case,” he stresses, “the answer is only there to reassure and to calm the viewer,” because, he continues, “I think the reason for a crime or an accident is always much more complex than what you can describe and see on screen in 70 minutes.”

Benny’s Video remains unsettling, perhaps even more so in this age of mass surveillance, social media, the internet, and image manipulation. So many people live on their phones or through screens, and A.I. is making it more challenging to determine the authenticity of a still or moving image. We have a tendency to document everything we see rather than experiencing life in real time. Interestingly, Haneke never takes photographs or videos on his phone or otherwise when he’s on holiday. His reason? “I think it is completely perverse!”

For my newsletter, I pondered whether anything is coincidental when synergy occurs, or whether some things are destined and meant to be:

https://sabinastent.substack.com/p/the-stone-door?utm_campaign=post&triedRedirect=true